|

|

Worked on during these and other dates: March 3, 1990, March 10,1990, July 19, 1991, June 21, 1992, August 7 & 8, 1993, February 27, 1994, April 14, 1994, July 30, 1995: 122,880 bytes, December 2, 1995: 104,960, December 3, 1995: 111,000 bytes stopped at 130,560 and beyond...

Rabbi Jeoshua Cassorla b. circa 1850 d. ? from Monastir |

Malkah Cassorla (maiden name unknown) b. c 1870? d. 1940 |

/ | \

|

|

||||

Buena (nee Cassorla) Passo m. |

Hyman Passo | Avrahm Cassorla b. c 1890? In Monastir d. 1970, age 80 in New York City |

Sophie Pesso b. c. 1897? In Monastir d. 1986? age 84 in New York City |

Jack Cassorla b. 1888? d. 1993 m. |

Lena Pardo d. 1997? |

|

|

Avrahm Cassorla b. c 1890? In Monastir d. 1970, age 80 in New York City |

Sophie Pesso b. c. 1897? In Monastir d. 1986? age 84 in New York City |

|

|||||||||||

Joe Cassorla b. 1916 d. 1956 m. |

Lee Cassorla |

Molly (Cassorla) Baruch b. 1/23/18 |

Jack Baruch b. 1/21/17 |

Lou Cassorla b. 1920 |

Betty (nee Camhi) Cassorla b. 1922 |

Morris Cassorla b. 1927 m. |

Selma Cassorla | Bessy (Cassorla) Hasson b. 1927 |

Ike Hasson | ||

Their children: David Cassorla Phillis (Cassorla) Clark |

Their children: Sylvia Baruch Phyllis Baruch |

Their children: | Raymond Hasson Arthur Hasson Josh Hasson | ||||||||

Sandra (Cassorla) Basoff (above as child), b. 5/8/47 m. Martin Basoff b. 8/8/45. Their child: Seth Bassoff b. Mar. 18, 1975 m. Their child: Sara Bassoff February 17, 2000 | |||||||||||

Albert Fried-Cassorla b. 1949 |

Kenneth Cassorla b. 1952 |

Marshall Cassorla b. 1956 |

Roberta (Cassorla) Ehrlich m. Martin Ehrlich. Their child: David Wagner |

||||||||

| Avram (also Abraham or "Papoo") Passo or Pesso | Bertha (?) Passo (maiden name unknown) |

| Born in Monastir, c. 1870, came to New York | Born and died in Monastir of asthma. Was religious and did not want to have her picture taken. |

|

|

||||||

Sophie Passo b. c. 1897? In Monastir, arr. In NY in July, 1915. d. 1986? age 84 in New York City |

Avrahm Cassorla b. c 1890? In Monastir d. 1970, age 80 in New York City |

Fina Passo b. c. 1890, lived in Indianapolis |

Sam Calderon | Hyman (Chaim) Passo, Lived in Indianapolis |

Rachel Passo (nee Saadi) (Her brother worked in NYC) |

Sam Passo, b. in Monastir lived in Indianapolis Had several daughters and a boy: Albert Passo |

Buena Cassorla |

Their children (See Avrahm Cassorla family tree) |

Their children: Albert Calderon Charlie Morris Pauline |

Their children: Albert Passo (born on boat to NY) lived in Indianapolis and CA Sophia Passo Charlie (Mishulam) Passo Isaac "Izzy" Passo Sara (nee Passo) Goldberg m. Robert Goldberg. Their children: Dan Goldberg Josh Goldberg Matt Goldberg |

Their children: Sarah or Sally Passo Molly Passo (lived in Las Vegas) m. Jimmy Nachmias Esther Passo Rebecca Passo Mary Passo Albert Passo

| ||||

My father’s father was named Rabbi Yeoshua Cassorla. As far as I know, he never came to the United States. He was considered a holy man back in Monastir, in the year 1900. Many people told me that because of his holiness, he had curative powers.

"He could practically cure you with a prayer!"

This was told to me by my grandmother, who did make it to the U.S. Mr. Cohen, who lived in our building at Rockaway told me this kind of story, too.

Yeoshua was a bookbinder by trade. His rabbinical training must have been informal -- they did not attend seminaries. Rabbinical lore was always handed down from father to son. I never saw a picture of him.

Albert adds: "In shul, I’ve heard his name mentioned by Rabbi Marans, and the congregation would acknowledge the mention."

Rabbi Marans, by the way, likes to tell the Yiddish congregations about my father changing his name to Mr. Kessler, to be better liked and patronized by the yiddishim.

Malka attributed almost miraculous powers to Jeoshua, in ability to heal

the sick. People came to Rabbi Cassorla and would have a drink of water,

and the Rabbi would say a prayer. According to Malka, in many cases the

people would revive. Jeoshua did not have a congregation, but was very highly

regarded by the people of Monastir. He was a bookbinder by trade. He had

a long grey beard. People would kiss Malka's hand here in New York, out

of respect for her being the wife of a rabbi.

Children of Rabbi Jeoshua Cassorla: Buena, Avrahm, Jack.

1885 - People in Monastir who were called "Chamal" - like a camel

Mickey Albuker's father was like chamal, Sammy's brother. Their brother

was Isaac. There is a man carrying thongs for you, although our friend Evvie

Eskanasi says it is someone who carries all he owns on his back.

In Monastir there were people with this job. This camel we knew was Ponte

Otto is. I could figure out how they charged, or how they could bring home

daily pay.

My father spent his youth learning to be a shoemaker, then said good-bye

before the time designated. He had a girlfriend before Sophie ,maybe in

1903.

It was customary when Yeshuah’s wife, Malkah, when she went to her pew in the upper reaches of the shul, to be approached by other women who would kiss her hand out of respect. This was because she was the rabbi’s wife. She was called a "rubisa."

This was a first marriage for her. She was an orphan, and Yeoshua married her becuase a rabbi is supposed to marry an orphan - it’s a godly thing to do. Yeoshua had grown children already from an earlier marriage. My father used to write pretty religiously to his older brother and send $10 each time.

He came to the United States with two ladies -- his daughter, and his future daughter-in-law.

Abraham (Avrahm) Cassorla - born circa 1891ce - died 1970ce. He married Sophie Pesso in 1915ce. We believe that Avrahm was the first-born of Yeoshua and Malka. Avrahm emigrated in 1910ce, passing through Ellis Island on his way to Allen Street on the Lower East Side.

Like many others of his time, he was fleeing Turkish conscription. Also, he was fleeing a girlfriend whom he did not want to marry. This was an arranged marriage which never happened. Also, he had reneged on his agreement with his cobbler boss to serve as an apprentice for several more years in Monastir.

As Avrahm once said of the inequity of the situation, "My boss would have paid me a pittance for a week's work, when I could earn as much fixing one pair of shoes in Monastir."

Avrahm became an antiques repairer. His first job was working for a gas fixture factory. He formed a partnership with an Ashkenasi worker of that factory, Motel. Married Sophie Passo in 1915ce. They married in New York. His family lived on the Lower East Side until 1928ce, when they moved to New Lots (now known as East New York). Avrahm did business for many years in Manhattan as Antique Gas and Electric Fixtures, later known as A. Kessler, Manufacturer of Synagogue Specialties.

Avrahm chose A. Kessler rather than Cassorla Hardware as his company's name, because Kessler sounded more Ashkenasi or Jewish. This was important in his line of work, where he specialized in Jewish religious items such as Menorahs, Chupas (wedding canopies) and Ner Tamids (Eternal Lights). He passed away in 1970ce.

Pop was 28 when he married Sophie in 1915. He came here in 1910. She came in 1915. The engagement was through the mails.

Unfortunately, I know little abbout them, my mother Sophie's parents.

However, his great gransson, Richard Pesso, writes: "As confirmed by

the ship's manifest, my father was approximately 8 weeks old when he "set

sail" for America. It also shows that the ship left from Petras, Greece

-- approximately 250 miles from Monastir -- on August 25, 1913. [My father

was born on June 28, 1913] So, it was still quite of "baptism"

for my infant father and my nursing Grandmother. My father always told me

that he left at 6 weeks old ... so, it might have taken some time to get

from Monastir to Petras."

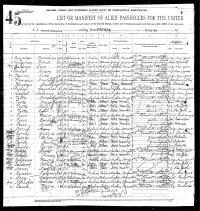

Below is a picture of the ship they arrived in:

|

Avram Pesso is known to have arrived on this ship, the Martha Washington, on September 8, 1913. It may well be that Betty's father Haim Camhi, also arrived on the same ship. Both men are listed on the ship's manifest. The ship was built in Glasgow, Scotland and was later renamed the Tel Aviv. This ship could hold 2,190 passengers. Of those, the vast majority were third class, which I suppose is also called "steerage." The point of departure is listed as Patras, Akhaia, Peloponnessos, Greece. |

|

SHIP's MANIFEST Click HERE to see a much larger view of the ship's manifest. See Avram Pesso's information on line16, and Haim Camhi's on line 20. |

As far as I can recollect, I've always been under the influence of Sephardism. Why? Because my entire building at 138 Orchard Street was occupied by fifteen Sephardic families and one hold-out: a janitor and his family who were Ashkenazy.

|

| Bessy, Avrahm, Lou in sailor outfit in his arms, and Joe. This shot was taken in 1924 and developed at "Radio City Photography Studio." |

Before I proceed any further, allow me to explain the word "Sephardim." Sephardim are Spanish-Jewish people, whose history dates back to the time of the Spanish Inquisition. They were forced to either covert to Catholicism, leave the country, or be killed. I was born to Sophie and Avrahm Cassorla in the year 1920. I was the third child. I followed my older brother Joshua, and my sister Mollie. All children in the area spoke Ladino a form of the Spanish language.

My earliest memory is going to Hebrew School at age 4. We lived on the Lower East Side, at the corner of Orchard and Delancey Street. Our family was religious, but not orthodox. At Hebrew School the form of punishment was to be hit with an 18-inch ruler, with which teachers hit the plams of our hands. Girls didn't get hit, and we boys were always envious of their privilege.

One of our traditions around the time of Passover was to play a game with hazel nuts. The nuts were in their hard shells. You dig a little hole in the dirt. Then you'd try to land an even number of nuts in a 4-inch hole. You lined the nuts up in twos in your hands and you'd try to roll them in twos in to the hole. We didn't wear yarmulkas.

We always wore knickers, but we were wary of getting holes in our knees -- our Moms would kill us if we got a hole. So we'd protect our pants by carrying a wad of paper along with us to kneel on.

My earliest friends were Abie Passo and Sammy Albucker, who lived in the same building. Both are still alive, Abie living in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and Sammy living on Long Island in Woodnere. From about ages four to eight, we played together. Abie hit the bigtime, and his family moved to posh Williamsburgh, Brooklyn when he was 7.

We used to play a form of hopscotch, called Potsy. You get an old tin of Helmar Cigarillos, and we'd bend it into a triangle. We'd throw the tin into the square we intended to hop into.

Skelly was a game where you drew a skull on a rectangle on the sidewalk, and you'd flick bottlecaps or checkers into number little squares along the big rectangle's edges. Bottlecaps had a sliver of cork, and we'd put two layers of cork in the bottlecap to give it weight.

My Hebrew School was part of the Congregation of Peace and Brotherhood of Monastir, a town in Turkey (now Bitola, Yugoslavia). There were about 3,000 or 4,000 people in the whole Monastir community.

I went to Hebrew School before I went to elementary school. How did this come about? Abie Passo was on his way to Hebrew School, and my Grandmother, Malka Cassorla, asked him to take me along with him. Malka was my father's mother. It was her first marriage: she had married Rabbi Cassorla when she was about 18, and he was in his 50's.

Therefore, I was introduced to the Hebrew Language before I knew my ABC's. Hebrew Schools back then had Old World-style discipline. Hitting with a stick was the only form of discipline for repeating an offense -- you'd get strokes on your open palm. Offenses included talking out of turn, eating in the classroom, etc.

We had to come in with a cap -- yarmulkahs were uncommon or too costly. So if we failed to wear a cap, you made a cap out of a handkerchief, making four knots on the ends.

Sometimes, if we got to class early, we'd find the stick on a ledge above the blackboard, grab it, and hide it! We'd hide it in our desk compartments.

I started Hebrew School at age 4. Our school attendance was required on Sunday through Thursday. Friday through Saturday, in observancve of the Sabbath, there was no Hebrew School. We attended for two hours. I stayed with the kindergarten kids, from two to four pm, or four to six pm.

I had Chacham (Rabbi) Varon, who was the terror of the school -- like Mrs. Kreegan in PS 190. One day, when we were attending services on a Saturday morning, he needed a handkerchief. He asked me to come up to him while he was at the pulpit.

He asked me in Ladino to ask his mother for a handkerchief. I thought "mother" and "wife" meant the same thing. I got him his handkerchief. His wife was in the house, because she had her own household duties. Women were not expected to go to school, except on the high holy days.

On any festive occasion, we all got excited in advance. It could have been a bar mitzvah, a wedding, or the naming of a female baby. Females didn't have birthdays, so this was the way their birth was honored. Usually, the women of the family would be given Jordan almonds -- candy-covered. They would throw them up in the air at a certain point in the service.

Then there'd be a mad scramble for the candy! Candy was not plentiful in those days, and we'd fill our pockets with it.

I remembered tearing my shirt in one of the scrambles. Back then, our shirts were made out of 25-pound Hecker's flour bags. They were made out of cotton duck. First our mothers would try to get the red Hecker's logo off the shirt material, but sometimes part of the logo would still show through, and you'd see an H or C of Hecker's in script. These shirts were comfortable. We always wore knickers and long plaid socks, of course. You didn't wear long pants till you were 13. All American boys -- not just Sephardics -- wore this uniform in the 1920's.

We learned to read Hebrew, although we rarely understood the meaning of the words. The object was to "read" from the Torah fluently -- even without comprehension.

The streets around Orchard Street were so crowded with litter, people and pushcarts, that playing space was hard to find -- impossible, in fact! We could never play stickball, because you couldn't swing a stick. You'd hit people! Orchard Street was the market for the entire Jewish community of the Lower East Side. This was the Jewish ghetto, and our section was Sephardic.

My parents were pretty free with us. At age 4, we were allowed to go out and play in the street, in the hallways, or in the backyard, where we were comparatively safe.

We lived in a four-story tenement, on the second floor. This was my parents' first place in the New World. The building was a cold-water flat.

|

If you wanted hot water, you heated a kettle over a stove. There were four families to a floor. We had eight people, three adults and five children living in a three-room flat. |

| Lou, age 4 - quite the sailor-boy! | Here was the floor plan: |

Bedroom for Avrahm, Sophie and baby Bessie

|

Kitchen

/ (front door) |

Living Room, also the bedroom for Lou, Molly & Joe & Moish and Malkah

|

|

We never wore coats indoors, so we couldn't have been that cold. Although, in April we might still be wearing winter coats outside. One April, when I was about six, we left our coats on our front stoop's railing. We wandered just a little farther down the block before we realized that we had left the coats.

When we returned, the coats were stolen!

Another time, I remember that a box was dropped off to the store below us. They left a box of shirt collars for the store. My friends and I stole the box and pried it open. We sold the collars on a street-corner! We made a lot of money. I had no remorse for what I was doing. What did I know? I was just a kid.

There was a park near the beach where underprivileged children stayed. We were not poor. We lived there. We had a nice trek to the beach. Everyone had the same shape bag which was for vegetables and whatever we brought along. I was maybe 7 or 8, and we had just moved to New Lots. Sometimes we had a stick and we put it through the handles of the bag to carry it. Molly got tired, so we wanted Mom to carry it. There was a water fountain with two spouts... the only drinking water we had around... the water dribbled out and we had to out our whole mouth on it to drink! Sometimes we'd miss a summer in Coney Island. We had a cabana, and I could even change in the women's locker. Then at 7 or 8, one woman was aghast -- I was too old now. My parents paid $10 for the entire season for use of a locker, which was worthwhile. Somehow we got separated... maybe 8 or 9 kids going through Seaside Park adjoining the beach. All 9 or 10 of us were hollering, "Moishe! Moishe! Moshie!!" There were seats and grass. Then it was getting dark already. He was maybe 4 and a half. We found that he was by the subway station at Ocean Parkway, and some people who were from New Lots saw him crying, so they took him home. We didn't see him until we got home. Somehow, we got word while we were still Coney Island, that Moishe was back in New Lots. |

|

| This is the classic Bar Mitzvah picture of my Dad's, taken in 1933. When my grandmom Sophie died, I asked to have this photo, which hung in her Rockaway apartment. This is a painted backdrop, with the edge of it visible behind them if you look closely. Top row, left toright Joe, Sophie, Avrahm, and Molly. Bottom row, left to right: Morris, Bessy and Louis.. |

When I was eight or nine years of age, the baseball results used to come in on ticker-tape, and the avid ball fans used to stand on the ledge of a barred window, peering into the pool room.

We'd look in , even though I was not that much of a ball fan. My landlord's son at 211 New Lots, Lazar Strauss, used to live and die by baseball. He was a Brooklyn Dodger fan. Those were the days of Babe Ruth. Gehrig was only a young upstart then.

We lived right next door to this poolroom. Why our mothers selected that site, I don't know. They weren't aware that living next door to a pool room could have a bad effect on us. However, the side of the pool room building was our handball wall. We played Chinese handball -- where the ball hits the floor first and then rebounds off the wall.

Chinese handball doesn't require as much space as a regular game. Then we started to use a wall of P.S. 190. There they had a brick wall and a lot of space around it which served us well.

By this time, we were 10, 11, 12, 13, or even 14. I would play for maybe four hours on Saturday and Sunday. We didn't have enough money to buy gloves, and would play barehanded. We'd often get a bone-bruise and have to lay off for a few weeks until it was repaired. We'd make makeshift gloves with any kind of gloves which we could find. We'd sew palm-patches on for extra protection.

By this time, we got used to playing with hardball rather than a Spalding, or as we called them, Spal-DEENS. We used a 555 brand handball.

My handball partner was Moish Copipo who was pretty inept at playing. Our opponents, who always beat us, were Hymie Baruch and Flash Elias. Jack Camhi sometimes came along, but neither he nor Eli Rousso were very much good. Hymie, Flash and myself were the best. Handball was our best and most steady sport. We'd try to pair off in a fair way. Our same group as playmates would be our handball partners.

At Rockaway, they charged us nickels and dimes to play handball on a real court.

|

|

the family has a good laugh! My father, Avrahm, was going around the house looking for chametz (food not kosher for Passover). He went around with a feather. I did not see him searching. He found a few slices of bahklavah that I had hid them on top of a closet at our house on New Lots Avenue. Half in jest and half in anger, with my Mom. He said: "Louyiku, que es estu? Ques es estu?" He was sort of excited at the discover, and amused. Bahklavah was my favorite food, only available in Purim, in January or February. So here it was maybe two months later, and I had probably had put it in a paper bag. I woundn't have left it exposed to dust. Everyone was laughing! Avrah, Sophie, Molly, Joe and even Moishe. Bessy was too young. I felt guilty that I was hiding what I should not have hidden. |

Swimming ability came because we used to spend successive summers at Coney Island. Coney was not a popular spot for Sephardics, who would congregate more at Rockway.

Why? I guess because we used to go there for my mother's health. She used to have nervous breakdowns when I was very young.

Once, she was hitting her head against the wall, out of frustration against the kids. I remember having a hell of a time, then vowing I'd listen to her and stay out of the way.

My mom and Betty were two real softies, who'd take any abuse from their kids. Not so much back-talk as making noise, running around and thinking we could get away with anything. And besides, having five kids and a mother-in-law living in three rooms can get pretty crazy.

From spending summers at Coney Island, I got to be a good swimmer. Then when I went to Jefferson, one of the first schools that had an indoor swimming pool (even though built in 1922 or so), I joined the swim team. Jefferson had graduating classes of 800, with eight sets of graduating at a time, 64,000 students in one school.

I made the swim team, but I wasn't all that good as far as speed was concerned. We'd monitor the other swimmers, to make sure they didn't have dirt between their toes! The water was freezing, and who wanted to swim in it?

At least I got mentioned in the yearbook for being on the swim team. I didn't like the meets because I didn't do well. I didn't meet women there. Our best source of doing that was the social club and occasional dances. I used to also sell the Liberty Bell, our weekly newspaper. When we graduated, they mentioned our extra-curricular activities.

At age 12, I met my soon-to-be good friend Callie at Bab's Poolhall at New Lots and Hinsdale Avenues. I also met two fighters, Boomy Davis and Schoolboy Bernie Friedkin. Boomy Davis once beat up a guy in Jink's Candy store with one hand tied behind his back.

Calllie and my Dad used to go to work together on the New Lots Avenue train. We would speak English together. When our parents didn't want us to know anything, they'd speak to each other in Greek or Turkish.

Back in those days, I was called "Big Lou," because Little Lou was Lou Calderon.

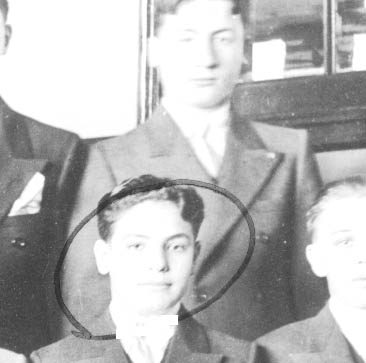

|

| My P.S. 190 Class, in Brooklyn. I'm the one with the circle around my head! This was taken in January of 1934, age 14. |

The first social club I joined was back in New Lots. I was already going to school. These boys in the club were mostly schoolboys from Thomas Jefferson whom I had met. All of my friends were working by then, mainly in the garment trades. The club was called The Nevele. It was in the finished basement of a home. We paid $13 a month for it. That worked out to a quarter a week per member.

Betty adds a bit of truth: "If you were a bad girl you went down there. If you were a good boy you didn't."

|

It was on Watkins Street. To lure the maurauding females, I built a box with lights in it. We used a Philadelphia Cream Cheese wooden box. It's about 16" long by 4" wide. I built a light into it and etched in the letters: "Club Nevele." I also installed a blinker. Our club was below street, because it was in a basement. We also had cards printed. My club name was Larry King. |

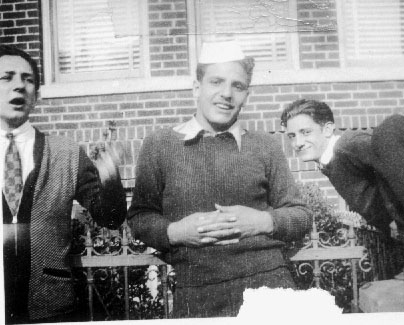

| Me at age 14. That's probably a halo. |

Milshe Copio became "Guy Costello." Joe Benson became "Joe Bensol." Their cards also said, FOR A GOOD TIME.

The club was mostly for dancing and kissing! It was either that or meeting in the pool hall. Women would stop by, get to know us, and then they'd be regulars. They'd come in bunches of four or five at a time. We only had refreshments if we had a party. There was cigarette smoking galore. Other clubs that were more tainted had marijuana smoking. We had brains enough to steer away from these things, being responsible Jewish youth. NONE of us took marijuana. They used to call it a "stick of tea."

In about 1936 or so, Hymie knew Moishe Copio from Hebrew School, but we didn't all socialize together. Our club room was in the process of breaking up. Hymie invited Moiseh to go down to the clubroom and join us to find another location for the club.

Then I was selected -- me and 3 boys, yiddishim who called themselves the three dukes -- to buy furniture to furnish the new club room on Miller Avenue. It was election day in November and we were off from school.

We hired a horse and a wagon. The cost was two dollars a day. I was afraid of the horse. The boys that I went with didn't go to school or to work. These guys didn't want a thing like that! They wanted to be bums! But they were good entertainers, with good voices. In the future, they'd help attract the people that we wanted to be in the club.

What they'd do is go down to the burlesque house in Brooklyn called the Star, and memorize the skits that the comics would perform there. Those skits were so good, I'd pee in my pants! My stomach would hurt from laughing so much!

Us boys, including Callie, Moishe Copio, Joe Benson, Louise Calderon (the best rider), and Jack Camhi, and I used to go to Hempstead and Forest Hills to go horseback riding. I would go to pick up Jack, Betty's brother, so that he could join us.

When I went, I wanted to see Betty's face, but she was shy and hid under the blanket. She thought she was unfit to be seen! I'd pull back the covers to see her face, gently, to tease her. She was about 17, and I was about 19. We'd go on these breakfast rides early in the morning. We'd go in for bacon and eggs and then go out riding again. Somehow bacon did not sound as un-kosher as ham. But it was a big treat to eat such good food! Bacon and egg with tomato on rye toast.

We'd say, "Give me a B & E on Rye-T!", sounding very professional. There was a favorite hangout for young people called Carole's on New Lots Avenue between Georgia and Sheffield. That's where we'd often go with a date after a movie.

A date often consisted of a movie, a sandwich and a coke! If a girl ordered more than a sandwich and a coke, she was acting out of place. At least I would take offense, and it would be the last time I would call on her. Three dollars was the amount of money that one would usually spend on a date.

|

| Here I am enjoying an ice cream cone with my buddies at about 17 years of age. We're at Coney island posing in a pretend car. My friends always wanted to go to Coney Island to look for girls. We'd never have any luck! I'd say, "Guys, if you want to meet ladies, go to a dance!" But they'd never listen to me! |

But then, we didn't date that much, either. Mainly, it was the expense of the date. We really couldn't afford it. Hanging out at the club was cost-free, and it was such common practice.

Hymie was going with Edna at the time, and I don't remember ever dating with them for that reason. Moishe Copio stopped being a steady friend of mine because he took up with Clara, whom he later married. So I hob-nobbed more with Callie, my favorite of the singles. This was when were were all around 16, 17, or 18.

One time, we were going camping and were all anxious to go. We had two cars. One was driven by Jack Hazen and one by perhaps Louie (the one that wasn’t in the accident).

We were on our way up to the mountain to this camping site. We had our whole gang in both cars. We were going up the West Side Highway, and I remember we were coming around a turn, and one of these city trucks, the back end was sticking out, came barreling around the turn! Our car hit it.

The car that got hit had Joe Benson, Callie, me and the others. Our car turned over a couple of times, rolled down an embankment and it landed on its roof. Fortunately only one guy had a little scratch over his eye -- Joe Benson. He was lying flat on the ground. I got hysterical, and I ran away. I think Sollie Cohen picked us up, and we sold him all our food when we came back to the club -- ten cents to the dollar. |

|

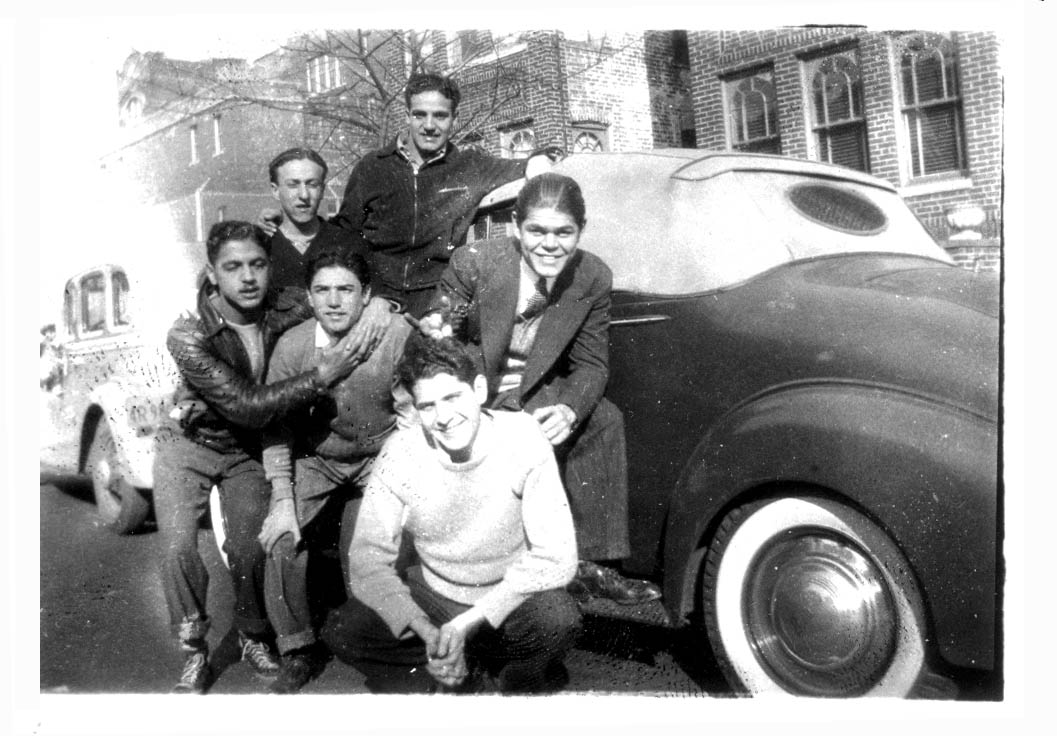

| Here's a natty bunch! That's Callie on the left, and me in the middle. |

Lou Calderon: "He enjoyed playing cards. And he was good at it. We used to play for hours. We played blackjack."

Callie: "We were like brothers, but when we played cards, we became very competitive. But we could stop for half an hour and talk about nonsense. Lou used to get angry because he wanted to play -- he took it very serious! He'd say, "Come on, let's play!"

Lou C: "Callie and I used to be partners with the dealer in blackjack, and we'd make bundles. But before we'd open our cards, we'd say, "Mary Bolen's kid sister, and I'd put my finger on his chin, for good luck. The first time we did that, we won! And about the 8th time, we also won! Lou reared up, and threw the cards all around and yelled, "What is this about MARY BOWLAND's kid sister!!!!""

First it was just Mary Boland, then her kid sister, and they'd win the pot! No matter what they did, they touched gold.

Lou Calderon: "What was funny was how angry he got."

Callie: "He was ready to tear the place apart!"

|

I borrowed clothing from my older brother, Joe. I had zoot suit pants that were so high, the waist band was directly underneath the armhole. You also had to have suspenders. It was a knock-off of a Harlem style. So in the yearbook, I was called "The Beau Brummel of Class 8A! |

In about 1938, Callie's uncle had a brand new Plymo (we caled it a "PLEE-mo", because of the pronunciation used by a sephardic man we knew named Angel Cazes. Angel was called "el es de afuera," meaning he was from outside Monestir.)-- a 32 Plymouth.

One of the features of the car was "floating power." That meant that the motor was suspended on a wire that put little or no thrust on the driveshaft. It was made for economy. It did 14 miles per gallon. You got 8 gallons for $1.05. We ran out of gas in the Lincoln Tunnel! We were 20 feet into the tunnel. It was Callie's car, and I asked for $1 apiece from all the passengers for gas. But $1 was not enough.

We were blocking traffic and everything. The guy behind us pushed us through -- being forced by the police to do so. In the car at the time were Joe Beonson, Shulie Aruti. Hymie was going steady already, and we didn't take these trips with what we called "married couples."

I was friendly at the time with Abie Barocas. We called him Abie B, which meant "bullshit," because he was a great exaggerater. We also called him twinkle-toes, because he was a good dancer at our social club parties.

Abie had a favorite lines: "Sangre de la patata grande!" It just meant blood of the big potato! But since it sounded latin, it sounded great. After all, Rudolph Valentino and Ramon Navarro were popular screen idols back then.

At any rate, we felt very fortunate to have the use of anything that resembled a new car. Callie, the borrower of this car, is still one of my best friends today. He was the main supporter of his family: he had a sickly father who was dependent on his chidren, because he had a bad heart.

Callie was also straddled with a brother who is somewhat retarded. The responsibility of maintaining a family fell on his broad shoulders at a very young age. The family was entirely dependent on him for their support.

But those were very hard times anyway. Abie B., for example, could not get the quarter up for their weekly dues! And I was still going to school, and I had no problem. I came from what I now realize was a richer and more affluent family than those around me -- certainly more affluent than Mom's. |

|

| April, 1937. Whoops! Double-exposure. We may not have been great photographers, but we had loads of fun. |

For instance, my sister Mollie, who was a sewing machine operator, would knock off work and go to the country with my mother because she refused to knuckle down to a sewing machine in the height of the summer. She was probably the only Sephardic girl who used to take two and a half month vacations. All of the others who needed the money that those arduous hours brought home to the family, continued to work.

We would go to our favorite place for the summer; our bungalow colony in White Sulfur Springs, in the Catskills. We visited it 10 or 15 years ago, and it's still there.

Me and Itzy were the only ones still in high school. Itzy Horowitz later changed his name legally to Harrow. His brother however, kept the name Horowitz, because he felt that a Jewish name was an asset in the medical profession. Itzy, being in the photography business, felt that an Anglicized name would be helpful.

|

| Here's the 1937 Gang! Clockwise from top, with me at 12 o'clock are: Lou, Eli Russo, Micky Martin (Moskowitz), Louie Calderon, Hymie Baruch, and Itzy Horowitz (Harrow). The car didn’t belong to any one of us! |

We changed the name of our group from Club Nevele to Club Pasadena. Anything Californian was a status symbol. The name Nevele came from the Nevele Hotel, locally. Pasadena reminded people of the aura of the Rose Bowl game. But the results were negligible in terms of attracting more females to the club.

Women stopped in by twos or threes, to the club that was riding high. But our club never rode high -- we were workaholics, taught by the industry. Bring home the bacon. In that sense, I was very privileged. My parents did not need any earnings from me.

In our graduation book, I was called the Beau Brummel of the class... I dressed very well, more maturely. I felt my attitude was more mature. I wore my brother Joe's clothes, his castoffs. But I pressed them and kept them looking good without undue expense. I pressed them with a hand-iron. You had to worry about a shine on wool, so you had to protect it with a damp cloth.

I aimed for that sharp crease. At that age already, I was lending Joe some money. Joe was self-employed. He had a little business called Buttons and Buckles. He'd find that business was slow, so I'd lend him two or three dollars. When I was 17, he was 3 1/2 years older, but 5 years ahead of me in school. He started in business at age 19. |

|

| My brother Joe Cassorla, circa 1946. |

Entry level for boys was the shipping department. I'm not sure how Joe got into the garment industry except maybe through connections with his friends who were in the business. Joe worked for someone else, for Silver Fox Sportswear with Ben Elias, later with our next-door neighbor on Alabama Avenue.

Alfassa was another man whom he was in contact with, a partner with Ben. Joe used to write love letters for Alfassa to give to his girlfriend. He was a high school graduate, and went to Brooklyn College at night, but he'd fall asleep in class

Eli, Hymie, Callie, Moishe, Louie Calderon, and Joe Benson were all working. I could afford to stay in school because my Dad was making a decent living. He didn't ask anything of his children. Sometimes we gave whatever we wanted to give.

I enjoyed ages sixteen to eighteen because I was accepted as an adult. I grew a moustache and colored it. If I wanted a lighter shade than I would get with a lady's eyebrow pencil. I modeled myself on Clark Gable. I admired Gable, incuding the picture

It Happened One Night with Claudette Colbert.

I've done a few foolish things in my life. Once I was going out with this girl who had a gap in her teeth, but she was still very attractive. She would come to the social club and we'd talk and maybe engage in a little petting or things like that. I was also with another girl at the same time. One day she confronted me as if she wanted me to give up this other girl and go to her. |

|

| That's Jack Camhi leaning over on the right in this photo, taken probably in 1937. |

I didn't know Leo Eskenazi then. We used to have a traditional rivalry of the New Lots versus the Sea Beach Sephardic boys. They'd arrange a baseball game at the Georgia hole playing field. It was on Linden Boulevard at the corner of Georgia Avenue. At the time, it was a vacant lot, and empty field that we had fashioned into a baseball diamond. Now it's a Coca-Cola bottling plant!

Maybe 35 or 40 kids total would be there playing softball, on a Sunday afternoon in May or June. It was a yearly thing. A lot of the kids came to play craps. Leo was the manager of the Sea Beach team.

He was blonde and white-faced, and we were used to a darker complexion among our Sephardic kids. I don't remember playing ball, because baseball was never my forte.

The smartest thing I could think of to say, not wanting to leave the girl I was with (just sitting with her), was, "Variety is the spice of life."

She didn't leave immediately. To this day, I wonder how she may have felt, because I've certainly given it thought. We'd see each other from time to time, but there was no feeling from then on. We both acted as if there was nothing between us. She wrote in my yearbook, "Variety is the spice of life."

There was a draft going on before the U.S. entry into World War II. There was the lend-lease program for England, where 50 destroyers were given to England

I at one time worked in an all-Italian workshop, Sam and Jack Pardo's shop, when I was 20. All you'd hear them singing would be the Italian fascist anthem. That shop was in the heart of Little Italy. Italian women didn't go to college -- they either went to beauty school or to the garment trade. There were no "horizons unlimited." I mention this to show how fascism was in the air, and how feelings in Little Italy were pro-Italy rather than pro-England.

I found myself all alone and was timid about expressing my feelings about Italy winning the war.

Sam, one of the men that I was working for, was a friend of my father's, a Monestirli, as well as Jakov, a brother in law of Sam's. This shop was called Renee's Dress Company. It's long since gone out of business.

In the meantime the draft had been in existence since about 1939 or 1940. You register for the draft when you're 21. None of my friends had been drafted. I made an appeal to be excused based on my eyesight, because I had an eye problem -- conjunctivitis. This appeal gave me a one-month delay before my being drafted.

This was a sort of half-hearted attempt to get out of the draft. In reality, we were all anxious for a change of life. My future didn't look bright at all. In fact, I had put in an application for a civil service job with the Sanitation Department of the City of New York. I had taken the physical exam for it in Staten Island, which seemed to me like a distant land at the time -- filled with truck-farms and Italian produce vendors.

One day in the summer, I was drafted. Me and Teddy Cohen got our notices at the same time. It said, "Greetings, the President of the United States and Congress welcomes you into our armed forces...." etc.

After I got the notice to report, I decided to take a one-week vacation. That was a common thing for pre-draftees to do. I went to see the play put on by the ILGWU called "Pinsadn Needles." It was quite successful, and I even knew someone in the cast. I went alone and remember feeling a little lonely.

People then didn't give up a day's work so easily -- not the way they do now. I was also worried about the disposal of my car, a 1936 Oldsmobile. I had gotten it with my lottery ticket earnings. I had $2,000 in the bank! That was a lot more than most people I knew.

I went galivanting or stood idly around my house. Times were pretty critical, even then. I remember reading four newspapers in one day, just to know what was going on in Europe. Things seemed helpless. Poland, the Netherlands, France, they all went down the drain to Nazism.

We were concerned for our own security. None of the information about the concentration camps had yet come out.

Teddy and I reported to our draft board. I also went with Sam Sansolo. I knew him from high school. Teddy was about a year older than I was. Most of the guys had hung around the house at least a year after registering -- but I got a call in July, which was only six months after registering.

So we went to the draft board, in a school in Canarsie. Old people were on the board. People up to 38 could be in the army. A lot of people had to hurry-up marriages to delay entry into the army because of their loved ones. For instance, my sister Molly got married. Molly was married and lived with my mother and father, because it was unheard of to live together without being married by a rabbi. |

|

| Here are Joe and his bride, Lee, circa 1946. |

The reason they didn't have a rabbi, was that they married on short notice. They later had a wedding ceremony in 1942, some time later.

There about ten or twelve men at the school where Teddy and I went to, to join the army. Sam Sansole was a volunteer soldier. There was a thought that if you volunteer, you had more control over your fate in the service.

Sam was put in charge of a group of twelve conscripts. We were still in civilian clothing, and Sam was like our unofficial sergeant. He took us by subway to the Long Island Railroad, where we took a train to Camp Upton. That was the Reception Center for conscripts. Camp Upton no longer exists. It was in Yaphank, Long Island, near the Brookhaven Laboratories. Also, Irving Berlin wrote a a musical song about it called, "Yip-Yip Yaphank." That show also included the song, Oh how I Hate to get Up In the Morning.

At the Reception Center, you're given the rudiments of many little skills. For example, how to make a bed. We got clothing, inoculation shots, and then got separated. After two days, I departed with Teddy Cohen the only person I knew there, and my group went to Fort Belvoir, Virginia.

I was there from November 15, 1941 through January, 1942. I was in training at Fort Belvoir, 40 minutes outside of Washington, DC. This place was just for training "engineers" - a term for pick and shovel work! There were ten women to every man in DC, and they'd bring them in by the busloads to join GI's for parties. We didn't even have to leave the base! I thought this was the way the army would be -- a bit of heaven! The women would cut in at dances with the men, unheard of in civilian times. I remember I got pretty close with a Jewish girl. |

|

| Hey, it's tiring defending the free world! Here I am during guard duty at Ft. Belvoir, January, 1942. |

This was the first time I thought I was more than a decent dancer. I had had some good training at our social clubs. I was head-and-shoulders above the other GI's in this respect, and as a result the girls liked dancing with me.

It wasn't unusual in New York to be a good dancer, but here I was outstanding!

We were called aviation engineers, meaning we would know how to build runways, tarmacs, quonsets, officer's quarters, and troop billeting structures made out of pre-fabricated steel.

|

| This shot may have been taken at the Copacabana Night Club. It shows me and Eli Rousso, as Navy man. The backdrop is painted. |

Headquarters company had the technical knowledge and we were the brute force. We learned little: nothing about electricity, construction with wood or steel, cement laying, or plumbing. They issued us Springfield '03's (a type of gun). They had been invented in 1903 and were used in World War One! The new Duran's had not arrived, so we had to receive the old guns. They were not gas-operated, like the Duran's, which advanced the next bullet.

It was a bolt-action rifle. We had to take it apart and put it together again. A rifle is basic. If ever anyone dropped a rifle, they'd get booed, and admonished by the higher-ups.

The cardinal rule was "never aim your rifle at anyone unless you intend to kill them. They had had too many accidents. We drilled and drilled until it was coming out of our head. It taught us discipline. We could feel ourselves improving.

Teddy joined me later at Fort Belvoir. Forts are permanent installations. Camps are temporary. Ted was ridiculed for poor handling of his rifle and everything. He and a little guy named Strouss were the butt of a lot of jokes.

The southerners, I found, took to the army more readily than we did. The cadre was all southern. When someone liked the army, we poked fun of them, saying, "Boy, you found a home in this army."

Even on a firing range at Coney Island, I had never fired a rifle. I had no desire to, but Betty did! She's always enjoyed rifle ranges. There's a method of learning marksmanship, where we'd learn outside of the barracks. Without even shooting a rifle, you'd know if you're shooting well or not.

When you'd go to the range, you'd be there for a day. Before you go on guard duty, you must know the ins and outs of a rifle. I got my rifle, and my gas mask. The discipline with both of them was very strict.

My hands were trembling before I finished my first shot. I fired a clip of six shots. The kick of the rifle was powerful. You learned how to protect yourself by putting the rifle in the butt of your shoulder. I was pretty good at it, almost from the start.

The responsibility for making boiling water, so that men could dowse their mess kits in successive cans, each one boiling, so that by the third time they would be really clean -- was mine.

From eight a.m. to noon, it was my job to get the boiling water into those cans. This was in a mess tent at the Rifle Range.

Try as I may, the fires would sputter, catch a little and not proceed much more than that. These were wood fires -- the idea was to adapt ourselves to living in the field. The men arrived, but these big cauldrons were tepid at best, because of my inability to get the fire going I was admonished. I was all by myself, and it was supposed to be an easy task.

The men muttered, "Who's in charge of these goddamned fires!?" The mess kits came out just as greasy as they went in. I was nearby, but ashamed to admit I was the guilty party.

We also had to go on obstacle courses. Teddy and Strauss used to argue with each other about every little thing. They were both clumsy. We had to climb a wall maybe fifteen feet high on a rope ladder. Then there would be barbed wire, which we had to go underneath. We had to practically burrow underneath it. They told us they were firing live bullets over our heads. It was sporadic, and I doubt that it was live, because they could have lost men needed later in combat.

We'd go on forced marches. One night, we awoke at midnight and went out to build a bridge across a river. We had never been trained and didn't know what we were doing.

We used to call the bridges "pontoon bridges," but the officers would just call them "pontoons." We went along with this; it was part of the training. We arrived at the site, and you could hardly see anything; no moon, no light at all.

I was charged by my officer to guard a road. I would challenge anyone coming by, and yell "Stop!" and ask for the password. GI's came through, some were "enemies", and so I challenged them with my bullet-less rifle. As I was doing this, I heard a thunderous vehicle approaching.

Before this, all I had seen was a solitary GI on foot! I said "to hell with my rifle." There are some basics: walk the post in a military manner, challenge anything in sight or hearing, and 8 other general rules. But I heard this thunderous noise, and I knew I couldn't stop this thing.

I could barely make out what it was. I hid myself in a ravine. This way I figured, he wouldn't see me and not flatten me like a pancake. It was a half-track, with tires in the front and tank-treads in the back.

Then I resumed my position, and along comes a solitary figure.

"Halt, who's there?"

"It is I, Colonel Kimberly." His very name made us tremble.

"Advance and be recognized."

Even then, I couldn't recognize him -- never having seen him before. You never saw the big shots. In all my years in the Army, I once saw a one-star general, and that was when I was in the PX in a hospital.

Many generals lived in Alexandria, because it was so close to Washington DC. We visited there, and went to the USO Club. I wasn't committed to Mom at this point. That didn't start until I was at Westover Field.

There was nowhere to go to be private, so I had no place to go with this Jewish girl I had met a few times. Her parents were just like Jewish parents in NY, the ones I was used to. They were trying to eke out a living with their.

I came to be impressed with the Jewishness of the people, or the business-like atmosphere that surrounds Jewish people. No matter where I went, I found that they were among the entrepreneurs, the owners of the factories. They had a high regard, at least outwardly from the general populace.

Over the course of a few weeks, Teddy Cohen and I were shipped out separately.

I was fortunate to be sent to Westover Field, although at that time I was disappointed.

|

I wanted to be in a more exotic, far off place, to see different cultures and people. Teddy got shipped to Ft. Lewis, Washington --as far away from home as you could get! From there, he went on to the Aleutians. He had plenty of time on his hands... he used to write me 12-page letters. While still at Ft. Belvoir, Teddy used to get into petty fights with a Jewish guy named Strouss. Once, Teddy and Strouss were penalized, and they had to clean the latrines with a toothbrush. |

| My best friend Murray Rosen. He's the only guy who stiffed me during my whole time in the service. For $5! |

One day, the lieutenant announced, "The following men, step out. Cassorla..."

Little groups stepped out.

We had two barracks bags, and our deep blue colored duffel. I still had civilian pants, shoes, shirt, and jacket. I sent that stuff on home to lighten my load -- thereby closing out my civilian career. Now I was completely a military man.

My parents never sent us anything. The love was there, but they didn't know to send military relatives boxes of candy, or anything. Once in awhile I'd get a letter, written by Molly, dictated by my Mom or Dad. They were short letters, naturally. There was not too much happening at the home front.

One of my soldier friends had a letter written by a Colonel uncle of his, and he was removed from our batallion. He went on the special schooling.

Using that as a cue, I tried to figure out if I had any important relatives who could remove me from the work as an engineer (which work I didn't enjoy). I wrote a letter to the commanding general, telling him of my expertise as a pattern-maker, which was at best very, very limited. I had undergone a mail-order course in pattern-making, very sketchy at best. But I tried to parallel my experience as a pattern-maker with that of a cartographer! Of course, my pleas fell on deaf ears. Right then, I realized the importance of an education. Having a college degree would have made me a "90-Day Wonder" officer. |

|

| Mmmm! Army food was so delicious. Here I am chowing down with my buddies on the Camp David firing range in near Wilmington, North Carolina, February, 1943. On the back of this photo, I wrote: "Rugged, ain't we." |

I saw that the educational requirements for officers was reducing as the times decreed (or the importance of the government getting enough applicants to fill their positions was getting higher). There were too few college-educated men. Being on an air base, I watched the requirements being lowered from a full college degree to be a full flying officer, to as little as one year of college.

Then they eliminated the one year of college and made it dependant on your IQ! Every soldier had an IQ test, though you never got the results. I always considered myself a notch above the average, so I thought I'd apply for cadet training at Westover Field, MA.

It takes time for anything to happen in the army -- I was there for six or seven months, maybe less. We were getting ready to ship out overseas, and knowing that my application would go astray if I was overseas, I went directly to the cadet board.

I told them what was happening to me. They said, "Well, there is nothing we can do at this stage of the game. You'll just have to ship out and see what happens."

I was part of the detachment in a camp, a former CCC camp. The camp had been abandoned. We had to build a control tower in forest country.

I was offered to go aloft, where girders were joined together. They were bolted in place. It was probably an amateurish way to join the girders together. But my method was to straddle the existing girder -- then with one hand holding on for support, to attach the girders to make a pyramid. I found myself very insecure, with one hand holding on for my very life, and with the other, putting the bolt in the new girders.

After awhile I found this was not for me. I suffer from acrophobia, and I refused to go higher. The lieutenant determined that it was a lost cause... he found other men ready, willing and able. Once, we were working in the woods, and the mosquitoes were like what you'd expect in a jungle! They ordered jungle gear, and with our skin protected, we were able to do some work -- maybe 50% efficiency, about as low as working with a gas mask. There also, I got the worst detail I ever had in military training. A kitchen grease trap needed cleaning I was hip-deep in rubber gear in a pool of grease and fat. I couldn't help but close my eyes and do whatever I was doing. |

|

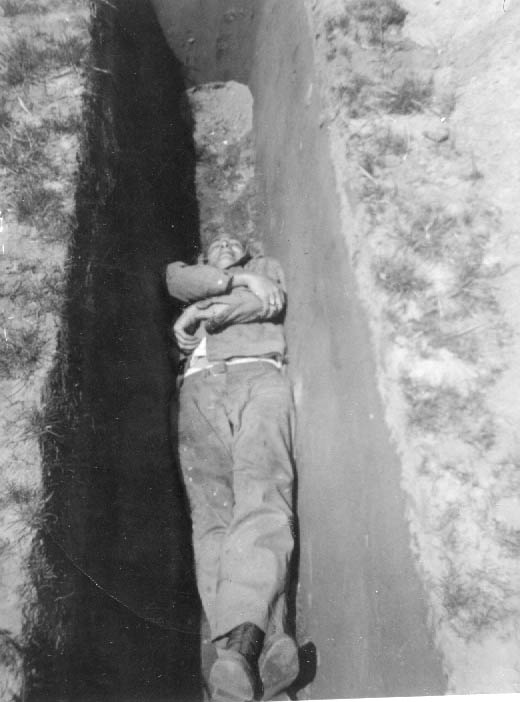

| Sleeping accommodations at Westover Field were rather basic. But if your Country asks you to sleep in a ditch, that's what you have to do! April, 1942. |

I vowed that if I was given a job like that, I'd refuse it, too. I would even brave the wrath of the higher officers.

On a bulletin board, we saw a notice that we were shipping out. So we got on a truck from the CCC camp back to Westover Field. We spent two or three days there and then we drove to Fort Dix.

I'd estimate it was 100 or 150 miles. All of the girls were waving to us... until the truck stopped, then they'd look away, and not make eye contact. These were open-air trucks, usually about twenty men to a truck. The officer or highest ranking non-commander sat in front with the driver.

At Westover Field one day, we had a major who summoned the entire batallion, of maybe 500 men, on a cold February day. He had just returned from Washington, DC. He says, "Men, I know where you're going, what you're gonna do, and we're getting you all ready."

|

| At the Latin Quarter in Manhattan 1942. Here's the gang on furlough. All of the men had come in on pass from the service. Roughly, from left to right: Julia and Eli Russo (Navy), Edna and Hymie Baruch (civilian), and Betty and Lou (Army) Cassorla. |

After he said this everyone started to cheer. A big whoop of joy and bravado went up. "Yay! We're finally going to see this war!" People were thrilled that we were going to get into the thick of action. I wasn't cheering though.

My thoughts were, "We're going from a safe area to a non-safe area." If I showed enthusiasm, it was feigned. I thought, these guys are happy that they're going to get shot at. These guys are crazy. But they have to show their spirit of patriotism and believe that they're going to do a bigger share by maybe giving their life to their country than being an ordinary citizen. I know that I was well off being stateside, and the longer I remained there, the better.

But of course I joined in at general elation at the idea!

We hadn't heard of any troops going to England at that time, though perhaps there were some in the Pacific. So we didn't have a clue as to where we would go. We heard nothing about English diplomats visiting Washington, or anything.

My mom and Betty got together and came to visit us, their last chance to see us before going overseas. Some guys went AWOL, but I didn't. Wrightstown is where they arrived and then they went to Fort Dix.

We got to Wrighstown from the bus depot in Manhattan. My Mom was now a big heavy lady, tall, but youngish enough to move fast.

The three of us went to the PX at Fort Dix, and we had a little meal together. Betty stayed away for a little while, so I could have conversations with my mother.

This was the time when I first began thinking of Mom romantically in a serious manner. We had maybe five or six hours together. I don't know why my father or brothers didn't come down -- there were lots of other families there.

Some soldiers cut their heads in Mohawk cuts, thinking they were going to the jungles. Betty says that when we were heading out to the bus, we were very concerned that people should not talk about this... that my mother was walking with my girl. This would cause people to think that she and I were committed to each other. So they tried to avoid traffic or people. But whom should they meet other than but Mrs. Russo!

Mrs. Russo had the world's fattest baby named Deenie (he later committed suicide). They were not a wealthy family then. Mrs. Russo saw my Mom and Betty walking together to the IRT. They were on Hegeman Avenue, not New Lots Avenue, a busier street.

So Dora Russo said, in Spanish, "Donde vas?" ("Where are you going?")

Sophie said, "We're going someplace, early in the morning. We're going to be late -- we have to meet somebody."

Poor Grandma Cassorla was so concerned that everyone was going to talk.

Another woman, Suzie Pardo, came over to Betty a few weeks later and said, "Are you going out with Louie Cassorla?" So Betty said, "Sort of." Making light of the situation. The word had obviously traveled, all from one encounter with Dora Russo!

I do remember spending a New Year's Eve with Mom, perhaps in 1940. But we didn't sustain the relationship.

Betty: "I felt sorry for Grandma, because I knew she wanted to be with her son. I started to walk away and let her have some privacy with Dad."

After she spoke with Dad, she said, "Betty, you come and talk with Louie now." And she walked away. I never forgot that.

It was tearful farewell, for all of us, when they had to go back. There's always the element of danger --we’d didn't know if I would come back alive.

I stayed at Fort Dix for maybe two weeks. I continued with our training: forced marches, calisthenics. We did maybe six or seven mile hikes.

After Betty and my Mom's visit, we just waited and killed time, getting bored. Until one night, we were awaked and told to get our gear ready -- everything that we owned went into two barracks bags. At that time, they were blue bags. Later they changed to olive drab green. Blue was a mark of early inductees - a kind of badge of honor. We were weighed down with these bags and put on trucks.

It was a hot night. We arrived at a pier and there standing in front of us was the biggest ocean liner of the day, the Queen Mary. We were in New Jersey, but didn’t know where. Perhaps Hoboken.

It was night time, lights were dimmed all over the place. Even the name of the ship was obliterated. It was a real prize. We had heard that the ocean liner was so fast that the dreaded submarines could not keep up. The British were having trouble with the U-boats, but they developed radar and sonar, and that saved hundreds of lives. Depth charges had wiped out many U-boats by then.

After getting on the ship, we went to our respective bunks which were set up with racks to accommodate bunks. Everywhere you went, all spaces were used. We trudged with our two barracks bags with our full gear onto the ship. There was a ledge seven or eight inches high from one area to another. We had been dragging our bags until then, and now we'd have to lift them to get over these bulkheads, which were used to seal off area of the ship in emergencies.

I was in Company B of the 809th engineers. Being an engineer meant we knew how to dig ditches, build foundations, remove trees. We were taught all of this at Westover, MA, where we built a control tower.

I had many friends now, but no New Lots boys. I lost my last New Lots friend at Fort Belvoir. I was chummy with an Italian guy, Carmine Mangano, a dark, handsome guy, who was very shy. He would get red-faced if we talked to a girl!

He had a nice nature and lived in New Rochelle. We were fortunate because we didn't have to go six stories high to get to our bunks. We had a little stateroom that the crew used to use, so there was no room to add any additional bunks.

All you saw were soldiers and beds and barracks bags hanging. The ship was built for 1,000 crew and 2,000 luxury passengers. Now had 20,000 soldiers plus crew!

I was disappointed when I found out that they had separate dining rooms for officers. We would peer in on them and see tablecloths and waiters taking care of the officers. Despite the difference in treatment, even under direct conditions like that, they managed to get their share of apartness and preferential treatment.

Our eating quarters were Spartan and smelly. British bill of fare was kippered herring for breakfast, but it was a good convenience food. The smell alone was enough to make American troops throw up, which they were doing all over the place. So fish and vomit smells pervaded everything. They had big pans of silverware and vomit, because the silverware pans were the nearest receptacle. Also, sea sickness was bothering men.

Life aboard the shop included the usual drills. They said, "Don't even throw cigarettes overboard, because the enemy will see it." Even in the barracks, we never threw cigarettes on the floor. We clinched the butts, scattered the tobacco on the floor and kept the paper, which we rolled up into a ball. We were taught to do this in camp.

At that time, just about everyone smoked. The tobacco companies gave free samples, 3 cigarettes apiece, tax free. Even if you were a non-smoker when you came in, you became one.

Uncle Jack Camhi was a smoker way before me. That's because he was working before me. When you're working, you're allowed to develop these bad habits. I even smoked cigarettes before my father, even though he smoked cigars. He smoked maybe one or two cigars a day.

Life aboard the ship was one pack of boredom. I carried around a Guinness Book of Records. Whenever I had an opportunity, out came that book of records, I was the biggest statistician around -- who had the most bunions, the biggest diamond in the world. This was for my own amusement. Throughout my career, I learned to carry a Reader's Digest in my back pocket. There was a lot of hurry up and wait in the army.

Card games were going on all over the ship, mainly poker and craps. Everybody had some money. The professional gamblers organized the craps games and they had most of the money. There was a small store on the ship with candy bars.

I noticed the lack of any cannons. There was one on the front of the ship, manned by a British crew, but none in other places. The defense of the ship depended on its speed. We had, for the first day out, destroyers accompanying us, either U.S. or British. But then in deep seas, we didn't see any ships. We figured that the authorities were well aware that a destroyer would be holding us back and that our speed was the best deterrent -- better than a warship.

We all had lifejackets. They were always nearby. They also had drills on the ship, in case we were ever sunk. The drills consisted of gathering at a particular place. We had to put on our lifejackets and go to a particular part of the ship. You'd know which lifeboat would be yours. Each boat would hold maybe 70 or 80 men. We didn't know who would operate the winches on the lifeboat, probably British crewmen who ran the ship would lower us.

We were on the ship for four or five days. We'd go on the deck and look for other ships around, but there never was anything. We knew we were heading for the shores of Europe, and figured it would be to England.

Nobody seemed to be worried. Everyone was confident of their safety. The last day -- which we didn't realize was actually our last --brought the appearance of accompanying warships on escort duty. We were in sight of land. We liked that. We could see seagulls coming to us. I was glad to see land. This eliminated the chance of the ship being sunk. We had heard about the North Atlantic, and how seven minutes in the water would kill you.

We landed in Scotland, in Gourac. We got off and went onto a tender. It wasn't a deep sea port, but it must've been the safest port. The general in charge of our army was George Marshall, who was chief of staff. Marshall was the only five star general. All the others were four star.

We disembarked into tenders. A tender handles about a hundred men with their gear. The water is deep and rucks waited for us and our bulky barracks bags. Disembarking wasn't like it was in New York. This was a small port, with no proper disembarking facilities. So we docked a few miles away, where the water was deeper.

They let us off at a lower level, so we went on a gangplank and onto the tender. The waters were smooth then. There were no battleships around, We found out later that it was the speed of the trip that enabled 25,000 troops to be transported. Every passageway was piled with cots. I was fortunate in that four of us were in a room, with 4 crewmen, one atop another. This was considered good facilities. We got onto US Army trucks, not British lorries and went to a former British encampment called Wittington Barracks. |

|

| My younger brother Morris, during the war. |

We were going to have training there, using the same facilities that the Birtish used. That's where I got lost! We hit land and I heard that there was a dance going on in town. I think it was our very first day over there. The trucks brought us into town, three or four miles away.

England was on double daylight savings time then. It didn't get dark until eleven o'clock. This way, working hours would coincide with daylight hours, to conserve electricity. I went to the dance and met a young lady who lived not far away. Like the brave soldier that I was, I took her home that evening. I walked her maybe half a mile.

I knew I was never too good with directions and details. I thought I would be able to ask someone, "Where is the Wittington Barracks?" But somewhere, I took the wrong road. I was walking and walking, looking for someone, another GI or an Englishman. It was midnight or maybe later. And I was hopelessly lost. I could hardly see the road in front of me.

I saw a light flickering from a house and I knocked at the door and heard scurrying at the house, but no one would open it up. I explained, "I'm an American soldier who is lost. I was at the dance at the palace. I'm looking to go back to the Wittington Barracks."

No one came to the door, even though I made enough noise to awaken them. The light went out, meaning, "Go away." They had been cautioned about German parachutists landing here and there, and they had been through the blitz the year before.

I spent the night walking until I finally found the camp, once it got light. Everyone had slept soundly, and we were getting ready to go out on a hike. Nobody missed me, so I had to go on a hike!

Apart from my college tutoring I was also in flight training. Part of my training to be an air cadet was to do a power stall. I was in a Piper Cub with the trainer. He was in the back seat and the plane had a dual control trainer so that he could take over if necessary.

I was nowhere near the level needed to fly solo. I had done only four or five hours before that. We flew 3,000 miles, mostly above the clouds. That way you can pick a place to land such as a road or a golf course. These planes were easy to control, and they glide easily.

The trainer said, "Put the plane into a steep climb." I pulled well back on the stick (It’s similar to a car going up a steep hill). The plane stuttered and labored heatedly. We knew it would stall. Our immediate reaction was to push forward on the stick, to level off. But he asked me to ignore that.

So the engine died. My heart jumped into my mouth. Now the plane headed downwards at a steep incline, but we were OK and got out of their alive.

This is where I washed out of the air corps cadet program. This could have been because of my lisp, or other reasons I don't know about. A psychologist listened to me talk and he made light of the lisp, saying, "Practice talking with a pebble in your mouth."

|

|

| Feb. 12, 1943, Ft. Belvoir. "All pooped after a hike." | To show you how joyous this experience was to me, we've included this blurry but revealing close-up. |

Here I am, fifty years later, and I still wonder why exactly I "washed out." I was so hurt -- hurt to no end! It was probably the biggest disappointment of my life.

|

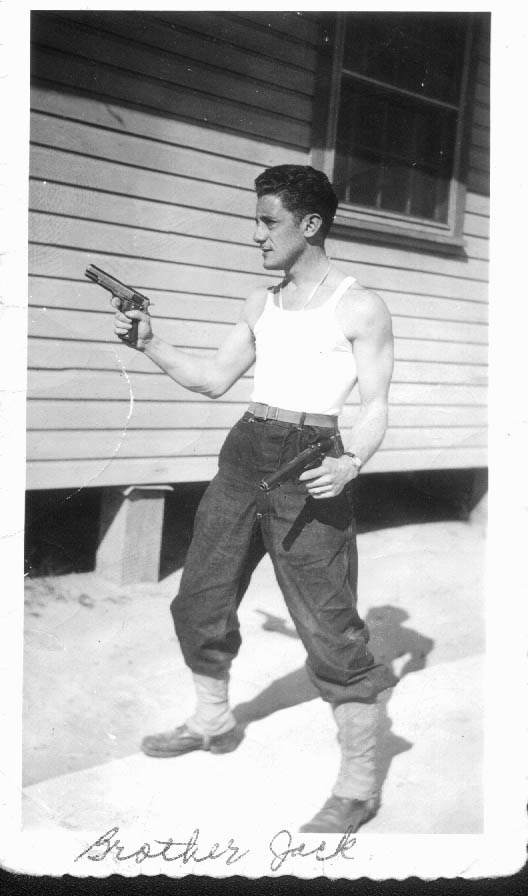

| Betty's brother Jack has his rifle inspected, about 1942. |

I joined the Glee Club to get out of doing exercises in the head-high snow. We had an almost all-Jewish choir, because the word got around that we didn't have to do PT (physical training) in the snow if you sang. I always made friends easily, especially with Italians. They hear my name in a roll call, and they might sidle up to me and say something in Italian. Sometimes, I’d tell them I was Jewish right away.

In most cases, I’d bide my time to see what indications they’d give me. One guy, Ciminello, said, "What are you hanging around with Murray Rosen for?" I then let Ciminello know that I was Jewish myself. He was a quiet guy -- he seemed surprised. I wanted him to be in my immediate circle, I liked single guys. Every married man I knew played the field.

Some guys liked to drink. I found that that was a good way to meet men or women. That’s where these guys took me. I preferred dancing, even at Salvation Army.

There was some type of contagious disease going around and we weren't allowed to mingle with the other students. There were about 40 of us and we had no schooling for two weeks. They kept us busy doing calisthenics. It was close to Christmas time.

|

|

| Betty’s brother Jack Camhi had a great sense of humor! Here he is, circa 1943, in a combination of World War I Kaiser-type helmet and Nazi emblems. Probably materials he picked up during his stint in Europe. |

After the sickness was over, the school burned down -- or part of it. Enough to disrupt us and force us to start over again. Another period of inactivity. I knew the Elements of Electricity very, very well!

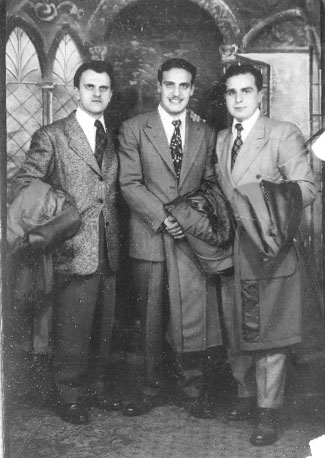

I was fortunate -- the only picture I have of the three brothers in uniform is a shot I took when I was with them. We had arranged to meet in Chicago. My older brother Joe was in school at Madison, Wisconsin. He was learning to be an administrator in Italy.

Uncle Morris (my younger brother) was also in the army. But somewhere along the line, he got out of the terrible infantry and got into the much more compatible air corps. It lacked that strict discipline of the infantry.

Moishe was passing through because he was going from one station to another, and he’d written to us. We’d covered on the phone and arranged to meet in Chicago. Joe and I got a hotel suite. We had gone to a dance the night before. Sunday, we would meet Moishe. Joe got up earlier than I did and went to the station.

What a nice awakening. When I awoke, there were Joe and Moishe! I hadn't been together with them in maybe a good couple of years. We asked, "Where you heading?" But of course no one had any idea half the time, especially if you're part of a larger troop shipment. Only the officers knew. Everything was hush-hush. "Loose lips sink ships" was the well-publicized motto. |

|

So we spent a couple of hours together We lacked a camera, but there was a single photo taken in a booth at the station. And then we had to split up at the railroad station. Joe and I left a couple of hours later.

Joe was undoubtedly the smartest man I ever knew. At age nineteen, he had his own successful business. He had his own circle of friends. His friends were intellectually below him, but he was a democratic person. He endeared himself to them. When he died, his workers cried as if he were their own son, or brother.

Benevolence was a good word for him. He was soft-spoken. He balded at a young age, and he blamed it on the sunlight he’d taken in at the seashore when he was younger. We weren't that close, because he was more of a father figure.

At Truex, I heard them talking about Moroni. There were three Jewish guys talking about Moroni. One was a high school teacher and one of the others was a lawyer. We were all in the ASTP program (Army Specialized Training Program) because we wanted to become a mayor.

We’d go to the Student Center or Social Center together where Moroni was the captain. Later on, I’d say, "Hey, Captain Moroni!" They later told me that his name wasn't Moroni. Moroni means "brown-nosing" in Italian.

There was nothing like the graduation ceremonies that they have today. When they thought you were ready, the shipped you out. This school was strictly for airplane mechanics. I showed a dis-inclination to fly even if this meant I could not be an officer. They wanted people to be all gung-ho on the flying aspect. If you don't want to fly instead, you could be a radio operator who would be more experienced in the mechanics of radio operation. No more Morse code for me -- even though I’d become very good at it. We’d have constant tests. If you passed with few mistakes, you'd go on to the next step.

I got what's called a "delay in route." In February or March of 1944, I got notice. Mom and I were in constant touch. But this time our romance had developed into "this is it." We would leave ten days earlier and were told to report to our new station in ten days. That’s when I told Mom that I would be going to Charleston, and I got a delay in route. "Let’s make plans for getting married," I said. In response, Betty said, "That’s a good idea, However, I've got the mumps." I was 24 and Mom was 22. My brother-in-law Dave was telling us not to get married on certain dates, because they’re holidays. |

|

Mom didn't have a wedding gown and there were no invitations. We had a three or four day honeymoon in Lakewood, NJ, a resort town.

Before we went to Lakewood, we went to the Prince George Hotel (right after the wedding). Mom had to rent a wedding gown for five dollars. I had my uniform, so that was good. It was a very pretty gown, but I had to give it back.

Prior to the wedding, Betty's sister Sally said, "Don't you have some kind of cape, or something to cover your wedding gown." So she loaned Sally her mink jacket. She left it in a cab before the wedding, and she started to scream. The driver stopped, and she gave it to her sister and said, "I never want to see this jacket again!" because she was frightened about mink.